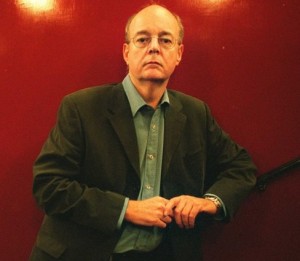

We talked to former WGGB President and acclaimed playwright David Edgar about his Iron Curtain Trilogy, which is being performed together for the first time to mark 25 years since the Wall came down

It has been reported that you sat down at your computer to start writing the first play in the trilogy, The Shape of the Table, the day after the Berlin Wall came down. Is that true, and how affected were you by that event?

It’s not completely true that I started the day after the Wall fell, though of course Eastern European communism had been crumbling for many weeks before the actual fall of the Wall. I was in Poland during the summer election campaign, which led to Solidarity taking over from the Communist Government, and was conscious of the sense that history was being made. The actual Polish election was on the same day as the suppression of the protests in Tiananmen Square (4 June 1989) and people feared that that was what would happen to the growing protests in Eastern Europe. But it turned out that the Polish election was the future, and the Tiananmen massacre the past.

The Shape of the Table is an interesting title. How did it come about?

During the Paris peace talks (in the late 1960s) between the Americans, the South Vietnamese, the North Vietnamese and the National Liberation Front (NLF; Viet Cong), the delegates spent nine months arguing about how the delegations would be seated. The South Vietnamese Government refused to recognise the NLF as a distinct party, claiming that their sole enemy was the North Vietnamese. The conflict was eventually resolved by a circular table at which the two national governments sat, surrounded by smaller tables for the other combatants. It seemed a good metaphor for the seemingly petty issues which actually have a huge importance in negotiations. In both The Shape of the Table and The Prisoner’s Dilemma (2001) breakthroughs are achieved by a tiny change in vocabulary.

There are three plays in your trilogy: The Shape of the Table (1990); Pentecost (1994); and The Prisoner’s Dilemma (2001). They were all conceived and written separately, over a decade, and focus on Eastern Europe during the post-Communist era. Is there one broader theme you explored in all of them?

I’m not sure there’s a single theme, but the three plays add up to a narrative: the first celebrating the victory of a mass movement over an authoritarian government, but suggesting that something important might have been lost; the second showing how the optimism of a newly unified Europe open to all was undermined by ethnic divisions, Western exploitation and fear of outsiders; and the third showing how those factors led to bloody wars breaking out across the region.

Did your opinion on the historical impact of the fall of the Berlin Wall change over the course of writing the three plays, and how was that reflected in your writing?

No, in the sense that it seemed like the greatest event of my lifetime, and it still feels like that (despite 9/11, which happened when the third play was in performance). What did change was how I felt about its aftermath. Like anyone human, I found the uprisings hugely exciting and inspiring (very much as those of the Arab Spring, which resembled them). As someone on the left, I felt that an important experiment had failed, and that that had impoverished humanity. Over the following years I became increasingly pessimistic about the ethnic and religious differences which emerged in Eastern Europe and beyond, which is reflected in the second act of The Prisoner’s Dilemma.

Do you think events of the past few years have given lie to the view at the time that the fall of the Berlin Wall represented the triumph of liberal democracy? And how, as a writer interested in politics, have you been reflecting the current challenges we face?

As I say, I think the overthrow of the totalitarian regimes of Eastern Europe made the world a better place, not least because illiberal and undemocratic regimes gave way to more liberal and certainly democratic ones. That’s the upside, and it’s a big one. The downside is that the ‘shock therapy’ economics imposed on the former Communist countries impoverished large swaths of the population, disparities of wealth became enormous, there were losses in terms of welfare and (in some countries) women’s rights, and there are now extreme right-wing movements in some of the former Bloc countries. I think you can trace both the move to the right in Hungary and the crisis in Ukraine back to the economic policies those countries were required to pursue by the West. My next play may well be about this.

It has been said that you enjoy challenging your audiences, particularly with long stories and polarising themes. Is this fair, and if so, why do you do this?

Well, my most successful show commercially (my adaptation of Nicholas Nickleby for the Royal Shakespeare Company) was eight and half hours long, and it continues to appeal to audiences in revivals in America and elsewhere. I don’t set out to polarise my audiences, but if you write on political themes, then that’s going to happen.

You have had more than 40 years’ experience writing for theatre, written more than 50 plays and been described as one of the most prolific modern playwrights. What keeps you motivated, and writing?

I’m a lot less prolific than I was: the spectacular numbers have to include many short plays I wrote at the beginning of my career. I now write fewer than one a play a year. But because I’ve been at it for so long, that adds up to quite a number. There’s a theory that playwriting is a young person’s game: I don’t agree with that, and I’m keen to disprove it by keeping going. I don’t plan retiring yet.

You founded the University of Birmingham’s MRes Playwriting Studies course in 1989 and were course director for a decade. What was the founding philosophy behind the course?

The playwriting course arose out of a number of self-help organisations set up by playwrights in the 1970s and 1980s to develop their craft. I wanted to try and codify those insights through dialogue with younger playwrights. The founding principle was that the course would be taught by practising playwrights (as it was and still is), and thus became a forum between emergent and more established playwrights to develop a language to describe what we do. My book How Plays Work (Nick Hern Books, 2009) is the result of these conversations, and the wisdom both of fellow playwrights who came and talked to the students, and the students themselves, three of whom have gone on to direct the course.

You were President of the Writers’ Guild of Great Britain from 2007 to 2013. What did you take from that experience, and why do you think trade unions have an important role to play today?

I am very proud to have been involved with the initial negotiation of two of the Guild’s three theatre agreements. We are currently involved in renegotiations of all three (too many to do at once). Without these agreements, playwrights would not be guaranteed upfront fees; they would pay a proportion of their future earnings to theatres that did their work from the first pound; they would have no right to attend rehearsals or to be paid for so doing; or to be consulted over casting or text changes. Improving and policing these agreements is vital for playwrights and the health of the theatre. This also applies to other areas where the Guild has agreements, including television and radio. Any playwright who works under a Guild agreement should join the union.

The Iron Curtain Trilogy, by the Burning Coal Theatre Company, will transfer from North Carolina to London’s Cockpit theatre (13-30 November 2014). Further details and bookings can be found on the theatre’s website.