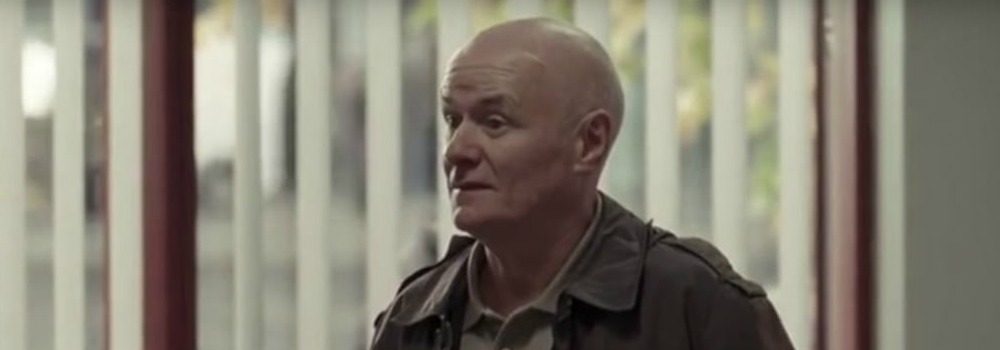

WGGB member Paul Laverty (pictured left) wrote the screenplay for I, Daniel Blake, which has its UK release this week. An indictment of benefit sanctions under the Coalition Government, its central character (played by Dave Johns, above), is a carpenter who finds himself in need of welfare after a heart attack.

The film won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this year and is directed by Paul Laverty’s long-term collaborator Ken Loach.

We spoke to Paul about his relationship with Ken Loach, his past as a lawyer, and the personal suffering he encountered during his exhaustive research for the film.

Could you tell us how your collaboration with Ken Loach started and how it has developed over the years?

I was working for a domestic human rights organisation in Nicaragua during the Sandinista years, when the United States was in the process of tearing Nicaragua apart through the foul work of the CIA. I was an eye witness to that war for over two years. The idea for a film script which eventually became Carla’s Song with the terrific actor Bobby Carlyle came out of that experience.

When I returned to Glasgow after two and half years in Central America, principally in Nicaragua, I wrote to Ken. He was open, curious, and very encouraging. He told me it would be a very long shot, but I should try writing a few scenes, instead of just a treatment. The treatment was important because it attracted Ken’s attention. But writing the scenes was a liberation. I wrote the first half of Carla’s Song very quickly. After that Ken and producer Sally Hibbin took it up as a project and after some time I was lucky enough to get my first commission, which was a big boost to any new writer’s confidence. But there was still a long, long way to go as Ken had three projects in front of that, so it took around another four or five years to make Carla’s Song. But I always had the conviction we would get it made somehow. Not many directors have the energy to head off to Central America, recovering from war, and are up for the challenge or making a film partly in another language where there was virtually no film-making tradition. I was innocent at the time, but looking back it was a great leap of faith by Ken. It takes courage to dive in like that, but that comes from his political conviction.

After that, one project just bled into another over the years. We have now done over a dozen films together with Rebecca O’Brien as our dynamic producer. The great advantage of working with Sixteen Films is the constant support, and mischief – never to be underestimated for the spirit of a creative team. I never take this for granted and feel very lucky.

You were previously a lawyer. How did the transition to screenwriter take place, and are there any parallels between the two professions?

After Nicaragua I had my fill of human rights reports and journalistic work too. Human rights becomes very politicised during a war, and the US Government is a past master of manipulating and telling grand lies about their role in Central America. They are still lying about it. Propagandist in chief of the big lie of course was Reagan, who boasted about the Contras, financed and trained by the CIA, as freedom fighters, despite their gross and systematic campaign of terror against the civilian population. Murder, torture, kidnap. State-inspired terrorism paid for by American taxpayers. In my youthful fury I wanted to try and make a film inspired by what I had seen. So it was a question of the gut, jumping from lawyer to writer, though it took a long time.

I learned a lot from my years as a lawyer in Glasgow, and my time at a human rights organisation in Nicaragua, but I was hungry for something else. After making one film, it becomes like a drug. You can’t wait to get stuck into the next adventure. The legal training was very helpful. Depending on the subject matter of the script there is often a great deal of research and digging up to do, just like in preparation for a trial. In a script too I suppose you are building a case, from someone’s point of view. So there is a lot of logical thinking to do. But that is not enough for a screenplay. You can’t copy a screenplay from the street. In one sense you have to forget all the research and then dive in looking for something original and unexpected. You have to look for odd combinations of ideas, perhaps off the wall. But that is the exciting part, being open in your daydreaming to ambushes. It is hard to describe, but you just hope the odd combination of ideas or characters comes along. And it might just stop, who knows?

How did I, Daniel Blake come about?

How Ken and myself work together is very organic. We are very close friends so we are always in conversation about things (mostly nothing to do with film) and sending each other cuttings or articles or whatever. The film before I, Daniel Blake was called Jimmy’s Hall, set in Ireland in the 1920s and 1930s. In period, every single frame, from someone’s hair, clothes, to the streets has to be recreated. In this new one we wanted to do something smacking of the contemporary, of the moment.

We were also very aware of the decisions made by the new Coalition Government after the banking crisis of making welfare a prime target for the cuts. According to opinion polls most people thought that up to 27% of the welfare budget was fraudulently claimed. In fact it was less than 1%. This gap between reality and perception was fascinating. Little wonder given the campaign of vilification against those on benefits. We found out from academics and NGOs that the disabled had suffered six times more cuts proportionately than anyone else.

But there was a key trip Ken and myself made to Ken’s childhood town of Nuneaton. Ken has a close relationship there with a charity that helps the young homeless get off the streets. Through them we talked to lots of young people. One young lad we met was called Jack who had a remarkable story. He had ended up in a zero-hour contract job. Sometimes he would get work on a little run, and then it would dry up. It threw his life into chaos. But in the most casual of manner he started talking about the experience of being hungry. Sometimes he would be without food for three days. It got us thinking about the working poor, those on welfare, and the rise of food banks.

It turns out that Jack’s story was very different from I, Daniel Blake, but the struggle for the basics, for food, heat and shelter, is somehow implicit. We sensed this new project would be raw and elemental. That and many other trips, especially to food banks up and down the country, set a tone.

Could you tell us a bit about the research process you went through for this film?

It was very thorough. It was a great challenge to get the functioning of the welfare system in the head. It is so different depending on the sector, whether disabled, ill, or just on the dole. Understanding the framework and legislation was one thing, but even more important was the lived experience of those who have to deal with it, both as a worker inside the DWP (Department for Work and Pensions) and as a claimant. It is a vast bureaucracy, and can seem overwhelming, even to those working inside it.

So we did some very serious investigation up and down the country, which included advisers, lawyers, trade unionists, whistle-blowers inside the DWP (which was key), doctors who spoke to us about their patients and the role of Atos and Maximus – the two multinationals who carry out assessments of the sick – activists outside the Jobcentres who helped vulnerable claimants, journalists, academics, disabled people. Those who worked in food banks, and those who attended. But mostly I spoke to people about their experiences, and what they had gone through.

The most difficult decision was where to place our story among all these options. Again, once informed by all the above and much more, the trick was to forget it, and look for a sharp premise, and then make the film’s journey simple, something we could do in an hour and 40 minutes. All the characters are fictional, but the story was informed, not copied, from so much we came across.

One reviewer has said the film has “shades of Dickens”, pointing to a moving scene in a food bank. How did the experience of working on this film affect you personally?

The stories of people in the food bank were unforgettable. Parents sanctioned for trivialities, and then feeding biscuits to their kids to keep them from hunger. Outrageous stories that would take far too long here. But as I listened to so much pain and suffering I did remember the words of Mr Neil Couling, a senior figure at the DWP, who stated that claimants “welcomed the jolt” of sanctions, and that the increase in food banks was about the poor maximising their “economic choices”.

The DWP, and their political masters, have been cynical beyond words. They reminded me of the spin of Alastair Campbell in relation to the Iraq war. They mentioned too they never had targets for numbers of sanctions. They perhaps never had a single figure in mind, but once again that is the good thing about doing the serious research. I was shown letters and lists by whistle-blowers of pressure on staff to carry out more sanctions otherwise they would be put on the Orwellian sounding PIP, Performance Improvement Plans! Or face the sack. You couldn’t invent it.

Let’s be clear, they have been liars, and some of our most vulnerable people have been the targets of sanctions. The charity Black Triangle gave me information on so many people who had given up and committed suicide. At the height of the DWP campaign there were around a million sanctions a year, though that number has now dropped. The pain and misery caused by all this is almost hidden from the record apart from the brave attempt by activists and trade unionists to bring it to the fore, but it has hardly penetrated public consciousness.

But it is key to recognise this was a political decision to target our most vulnerable. In the words of one civil servant, “low lying fruit”. Just like it is a political decision to go easy on the Apples, Amazons and Facebooks of this world in relation to them paying their fair share of tax. There is a difference between superficial legality and gross immorality.

Do you have any tips for screenwriters who are just starting out?

Watch your back. Learn some yoga. I am deadly serious!

Cinema is a complex, fragile, magical process requiring skills of all sorts. If you can find key collaborators who share your obsessions that will nourish you beyond measure. Loyalty is a beautiful virtue too.

You are a long-term member of WGGB. Why do you think the union is important for screenwriters and why are you a member?

This is the simplest question of all. We have to look after each other. True for work, true for life.

I, Daniel Blake is in UK cinemas from 21 October 2016.

Watch a preview of the film:

Photo of Paul Laverty: Shutterstock.com/Denis Makarenko